Writers' artefacts

Recently I watched a documentary about Gerhard Richter which recorded him painting some of his phenomenal abstract paintings. When I see them, I think of forests, of cities, of peering through disturbed water to glimpse... what? They have a depth and mystery that I love. Here's my favourite, St John (1988).

In the film, Richter filled a few huge canvases with broad strokes of vivid colour, then drew a giant squeegee across them in planes, loops, and arcs. He worked slowly and deliberately, and even though there was nothing surprising to me in his process I felt a touch of wonder watching these beautiful, complex images emerge from blankness. It felt as if he was opening a portal in front of my eyes.

I'm very interested in the creative process of my favourite writers too (of all writers, quite frankly!) but I imagine there's not the same kind of drama in watching someone hunched over a desk, scribbling, sighing, staring into space for a while, making a sandwich...

Even the greatest works of literature have wonderfully mundane origins. The tools that writers use are the same we use to make a shopping list or send an email to cancel a software subscription. Unless we're lucky enough to have a writer's shed or a study, chances our the works emerge from the sofa, or on the train, or at the kitchen table.

I find this amusing and oddly reassuring. And I think this lack of theatrics in the creation of our art contributes in a large part to the mystique of being a writer; there is something rather magical in the fact that putting one word in front of another in a very ordinary way can result in something extraordinary. There's a kind of alchemy there.

As regular readers know, I'm very interested in haunted objects: the associations that everyday objects acquire can feel almost supernatural at times.* Over the last few years I've happened to visit the homes of a few Great writers and thinkers, and had the chance to walk around in their rooms and look at their stuff. It's a fairly random selection so far. I visited Shakespeare's birthplace as a teenager, and the homes of Woolf, Austen, and Keats are on my to-visit list. (There are a lot of writer's homes open to the public, and of course a great number that are missing.)

There are ghosts in these places, for sure. The surfaces and spaces conjure the people who lived there, like all old houses. We can easily imagine their hand on the banister, their step on the stair beside us. But unlike every old house, we know these ghosts, or we feel that we do, and the small, bare rooms are overlaid with the worlds they created.

Objects can become a focus for the slightly homeless sense of wonder at the writer's creative process. Manuscripts and notebooks definitely have this kind of power - look! Angela Carter's notes for The Bloody Chamber - and so do desks.

When Charles Dickens died in 1870 he was an international literary celebrity. In response, artist Samuel Fildes created a watercolour painting showing the empty chair and desk in Dickens' study. At the Dickens Museum in London you can see the desk, and you can see the chair, and you can see an engraving of the painting too.

I am fond of many of Dickens' works, and I recognise the importance of his work in shifting Victorian attitudes to poverty, but he is not a figure that I personally admire (not least because he attempted to institutionalize his wife Catherine with false claims of mental illness so that he could pursue his affair with a younger woman - classy!) But there was something eerie about standing there with these artefacts. I felt it. An aura of some kind around these relics.

Pleasingly, at the museum you can also see Dickens' hairbrush, Dickens' chair, another Dickens' chair, Dickens' suit, Dickens' mirror, Dickens' bed, Dickens' commode... The commode was not especially inspiring, but sometimes it is surprising items which are the most charged.

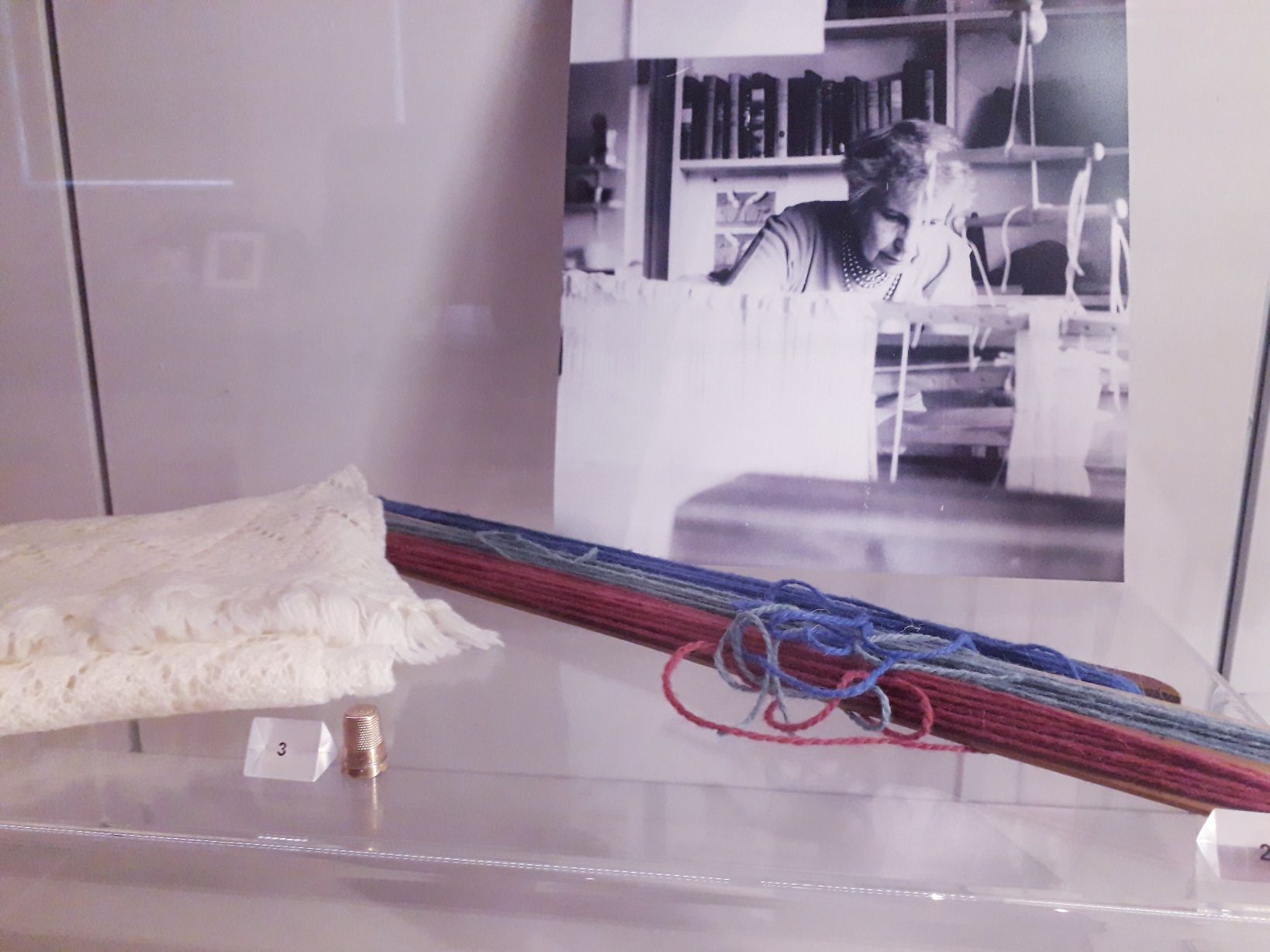

Me, haunting the Charles Dickens Museum. Dickens' bed. Samuel Johnson's attic and writing desk. Charlotte Bronte's bonnet. Sigmund Freud's begonia. Sigmund Freud's glasses, pen, and boots. Anna Freud's golden thimble and weaving. Bronte dining room. Darwin's greenhouse.

At the Brontë Parsonage Museum in Haworth, the Brontës' home has been recreated as closely as possible, and includes a huge number of their personal possessions. It was a remarkable experience standing in their little dining room beside the table where Emily Brontë wrote Wuthering Heights. I was moved to be there, and to see the physical embodiment of the cramped space and constraints they lived within, such a contrast with their vast, wild imaginary worlds.

However, the object that I felt the strongest reaction to was Charlotte Brontë's bonnet. I think it was the intimacy of it, but also the style of the bonnet and the way it was displayed gave me an uncanny feeling of her presence. As if the bonnet turned a little this way I might see her face.

I can understand why the personal effects of authors we admire take on this power. There is something ineffable about imagination, and something very mundane about writing, and bridging the two is a human being, ordinary and extraordinary at once.

When people wonder at the obscure magic of writing, they often locate it wholly in the genius of the Great Writer.** But I feel that that's missing the point. As Wolfgang Iser put it, "the convergence of text and reader brings the literary work into existence".*** The secret sauce in any work of literature is you.

*I've just added a haunted tea set to the list of cursed or haunted items in my fiction repertoire, alongside a glass fruit bowl, an antique camera, and a plastic skull.

**There are many problems with our common understanding of genius, such as the "golden-nugget" theory of genius identified by Linda Nochlin.

***This is of course true for visual art as well. As neuroscientist Eric Kandel says in this Big Think video: "You have a painting. That painting is not complete until the viewer responds to it."

Member discussion